Paris, Aug 17, 2017. Image credit: RC.

Paris, Aug 17, 2017. Image credit: RC.

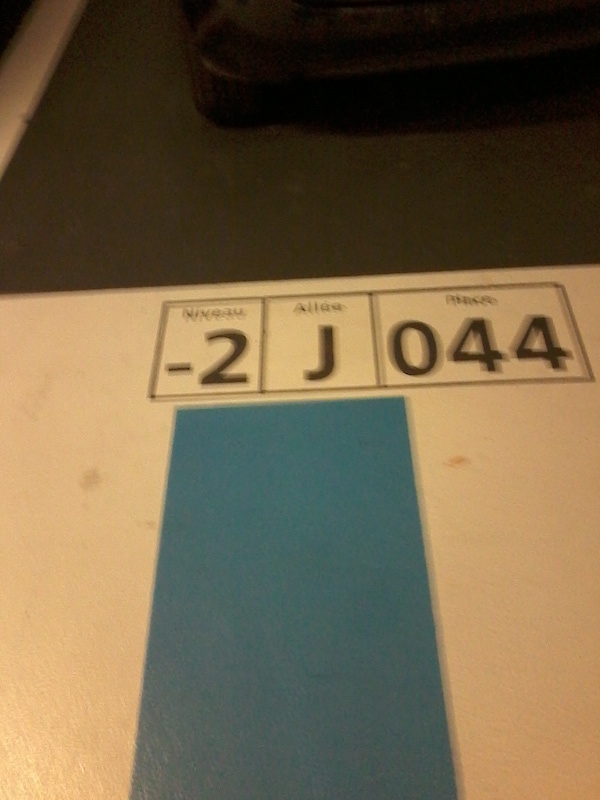

It happened before. You parked your car. When it came to collecting it, you wandered endlessly in the parking lot. This time you will pay attention, and memorize the spot – luckily, the owners of the parking provided names. This time, you are at -2J044. Level minus two, row J, number 44. Very logical. But how about memory? (Taking a picture, as many of us do, is a symptom that something should be rethought with this style of place naming.)

Some have taken place renaming seriously. Starting from the assumption that you cannot give longitude and latitude coordinates for parking spots (that is, you can, but these are pretty clumsy to register, and they are not indexed for elevation, which makes trouble when parking lots have superposed stories), alternate systems of addresses have popped up recently. A review of relative advantages and disadvantages has been published.

Places have names: Lombardy, Pacific Ocean, Case Rotte, Ljubljana, Via del Campo. These are names that are memorable in the context in which they are used. Some are almost iconic names. Place de la Concorde tells us about Paris, Via Veneto about Rome, Times Square about New York and so on. Some are names of objects (in the broad sense) located in the places in question, and sometimes signal ancient properties or relationships: Towerhill, Ellery House, Lake Constance. Some borrow their names from the names of other places. There are almost 30 Berlins in the US. One could write a whole book on why places have these kinds of names, on the history and evolution of place names, but the fact remains that it is useful to give a name to places, not so much to orient ourselves, but to efficiently communicate information about the places we are interested in, and that in this communicative practice the context helps us to find a place by its name. There is a Via Verdi in Milan and a Via Verdi in Rome, but if you are in Milan and ask for Via Verdi you do not need to specify that it is not the Via Verdi in Rome that you are looking for.

If you go and look up Douala in Cameroon on a cartographic software, you will notice that the network of roads is huge but place names are rare. A few years ago, a group of artists even created a project to install urban sculptures at strategic points in order to recall the spirit of the place (“The accident of the overturned truck”) and make life easier for the inhabitants - in particular for taxi drivers - in the absence of precise addresses.

Of course, we can also use the coordinate system (latitude and longitude), which unequivocally identifies place names. We have been doing this for centuries now, they allow us to put the earth in relation with the sky and to find our way on earth through the sky. The whole geography we use today is based on them. It certainly requires some learning, and perhaps the school system could invest more not only in the transmission of basic notions, but provide a real educational module on navigation (how to dead reckon, how to trace a route). Few are those who know the coordinates of their home address, even if only approximate, and very few who know the coordinates of any place rounded to the tenths of a second. It’s a pity that most commonly used maps - the tourist maps of a city, for example - don’t take the pain of inscribing the coordinates at the edge of the map.

Even the GPS - which lives on coordinates, incessantly grinding them - uses very indigent user interfaces, all things considered, in this respect. The first models gave only the coordinates; the last ones show by default maps without any indication of latitude and longitude. To facilitate readability, of course - and for the perception of a substantial uselessness of this information.

After all, why care about knowing that we are at 47°30,25’N and 4°12,25’ E (and by the way, who could say where this point is?). The trend is so unstoppable that today there are apps that propose to replace coordinates with an “intuitive” geocoding system. Dividing the earth’s surface in a set of squares of three meters side and giving each place a trio of names (such as “cheaper.notice.booster”) would solve the problem of telling your spouse where you parked your car (in Via Veneto in Rome). What3words does this thanks to proprietary code.

But places must be respected. Their structure is made up of contacts, distances, forms, part-whole relationships: it is primarily a mathematical structure that any respectable system of representation tries to capture. This structure belongs to no one and is therefore available to everyone, it is democratic, robust and reliable precisely because it is controllable. Sending an app a location request means giving up understanding where we are. And to give up is to give up, that is to say to accept to lose control over some aspects of the activity we are carrying out. I trust GPS because I have an idea of how it works and the kind of investment that several governments and the international scientific community have made in developing it. I check the latitude and longitude system because no one has it and we can all check it: it has a mathematical syntax.

And if you use ordinary language as a vector of geographical information, you have the problem of spelling. It’s true, Marco could say that he found London beautiful and Londres sad, not knowing that it’s the same city.

It is also true that if I want to use names to talk about a place, it is better that I do so in my own language, just to avoid misprints, or even just to minimize the impact of these, since one makes mistakes in one’s own spelling. The app we describing proposes many languages, just to not confine itself to the English market. On the one hand, this will end up ghettoizing geography, since it is the communities that decide which language to use to describe the places about which it is worth communicating; on the other hand, it will create duplications or worse: already now the Statue of Liberty is at an address called planet.inches-most in English and défiler.fusil.revisser in French. (In all the languages of the world the Statue of Liberty is at 40˚41˚21˚N or 74˚2˚40˚W.)

Finally, we must ask ourselves – as we are in the delegating mood - why not even propose a system of localization that we can use without even the intermediary of the name of the place. The BMS embarked on boats already propose to signal their position by pressing a button in case of emergency (for example, there is a button for man over board or MOB, which stores and signals the place of an accident.) There is no need to say anything, to memorize anything.

Perhaps the developers of the three-named system want to leverage the fascinating desire to own a place by owning his name. However, the last word here should go to an assessment of cognitive costs and benefits. What3words is very robust on the communication channel, so it may be interesting to use it when the channel is noisy; the coordinate system is very poor on the communication channel. On the other hand, what3words is very poor in the inferential context, as you cannot infer the relation between any two places in space by looking at their names, which is the great advantage of the coordinate system.